Stay up to date by subscribing to our Newsletter or by following our Telegram channel, and join the conversation on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram.

Edited by Marco Nurra

Aiming for novelty in coronavirus coverage, journalists end up sensationalizing the trivial and untrue. Journalists rushing to amplify any small update can mistakenly inflate its importance with sensational headlines or hyperbolic broadcast framing. For example: the widespread discussion of hydroxychloroquine as a “miracle cure” — it wasn’t. Traditionally, editorial news assessment of presidential assertions was simple: if the president said something, it was, by definition, newsworthy. Yet the COVID-19 pandemic has revealed how journalism’s traditional bias for novelty can result in front-page, top-of-the-broadcast news stories that are provably inaccurate, and even occasionally fictional. The tendency of journalists to inflate the value of certain new information makes the media manipulable and easy to exploit. President Trump realizes this. That’s why he tweets so much. He understands the content of any tweet is less important than its immediacy, and how his tweets pressure journalists to amplify unimportant messages on social media.

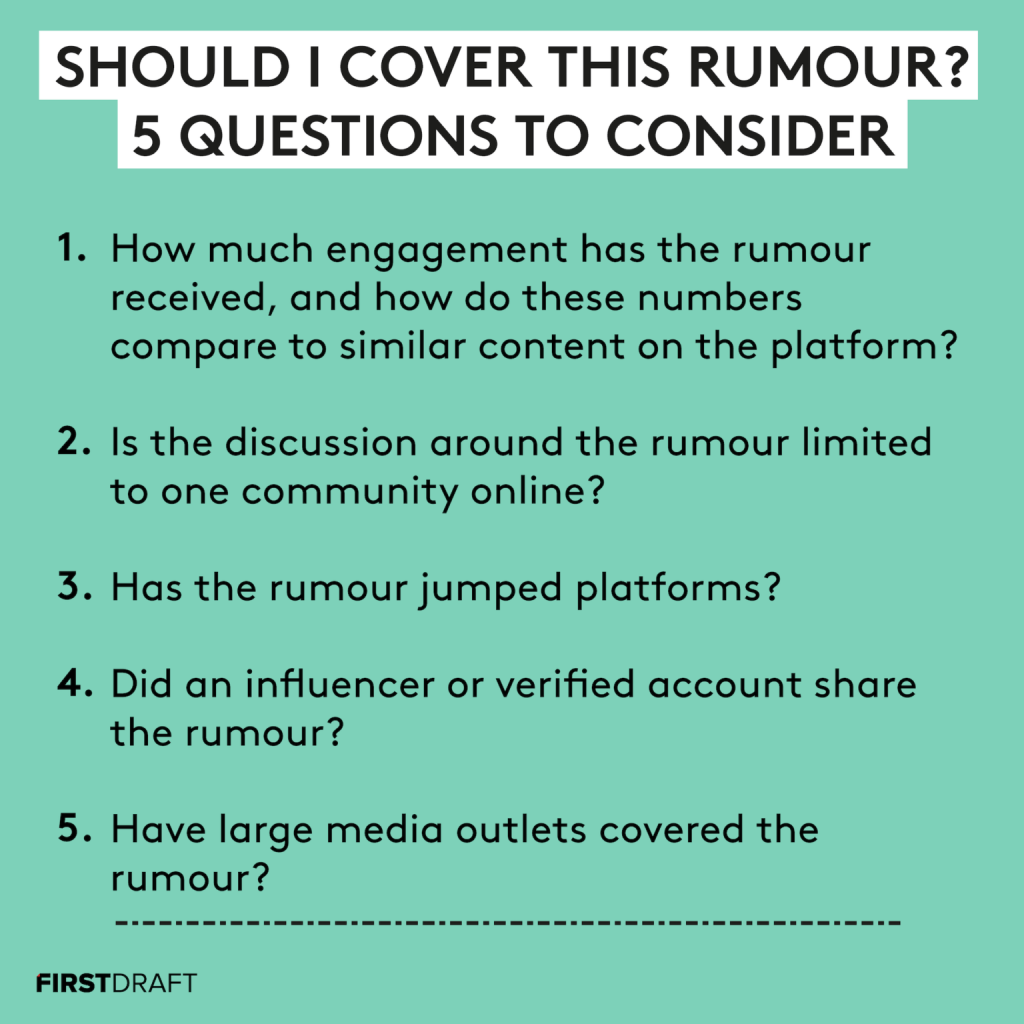

Ethical questions for covering coronavirus online: Be aware of the ‘tipping point’. From false links between 5G and the coronavirus to conspiracy theories around a potential vaccine, a huge ethical consideration for journalists is to avoid amplifying dangerous or misleading information. Claire Wardle cited the recent case of the viral “Plandemic” video which contained a number of falsehoods. While initially some newsrooms avoided reporting on it for fears of “giving it oxygen”, the video eventually gained so much traction that reporters realised it needed mainstream coverage. It’s not always straightforward to decide when to cover mis- or disinformation. For this, Wardle has coined the idea of the “tipping point”. On a case-by-case basis, there are a number of questions to ask before covering misleading content:

The fake ‘Obamagate’ scandal shows how Trump hacks the media. “So now we find ourselves engaged in an endless game of whack-a-mole, debunking and explaining one false claim after another. And false claims, if they’re repeated enough, become more plausible the more often they’re shared,” writes Vox’s Sean Illing.

The media is helping Trump turn the bogus ‘Obamagate’ into the 2020 version of Clinton’s emails. “It’s becoming clear that journalists never fully reckoned with the mistakes of 2016 campaign coverage. We know this because they seem poised to repeat them,” writes Margaret Sullivan.

Medical journal says Trump is ‘factually incorrect’ about when it first published coronavirus reports. The prestigious medical journal The Lancet fact-checked President Donald Trump over an allegation he made in his letter to the World Health Organization threatening to permanently cut US funding as the world is still fighting coronavirus.

New York Times reporter Davey Alba on covering COVID-19 conspiracy theories, facing online harassment. “As the virus progressed, [disinformation and conspiracy theories] became more organized and coalesced around certain topics, certain figures, certain specific rumors. Since then we’ve written specifically about [Microsoft co-founder and philanthropist] Bill Gates, and how a lot of conspiracists see him as one of these global elites who is trying to control the population given his past work on vaccines. Another one is [director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases] Dr. Anthony Fauci. Once the false narrative about him went truly viral, he had to get a security team because he started getting death threats. The president of the United States is a very central figure in coronavirus conspiracies. That was another flashpoint and cause for that campaign of harassment against me.”

The Atlantic’s executive editor talks conspiracy theories and journalistic norms. Nieman Lab interviews Adrienne LaFrance about her cover story on the conspiracy theory QAnon and how conspiracies — and the Trump presidency — have changed the way she thinks about reporting and editing. “There are all kinds of norms that have been shattered by this presidency where journalists are having to rethink how we do things. I certainly tend toward covering what’s happening and not shying away from controversial or disturbing truths. But it’s important to be very clear, for example, when you’re covering conspiracy theories about what’s true, what’s not, where there’s evidence, and where there’s not.”

The long, strange history of Bill Gates population control conspiracy theories. How the billionaire philanthropist displaced George Soros as the chief bogeyman of the right. Gates, who has announced that his $40 billion-foundation will shift its “total attention” to fighting COVID-19, has been accused of a range of misdeeds, from scheming to profit off a vaccine to creating the virus itself. On April 8, Fox News host Laura Ingraham and Attorney General Bill Barr speculated about whether Gates would use digital certificates to monitor anyone who got vaccinated.

One America News is the straight truth for Trump fans, and completely surreal for everyone else. To watch OAN is to experience the Trump presidency the way Trump himself would cover it, if he built a network from the ground up and then, as he did with his administration, hired amateurs to run it.

Americans who turn to the White House for coronavirus news tend to think the media’s pandemic coverage is overblown. A new Pew Research Center report found Americans’ views of the media’s coronavirus performance differ substantially depending on which sources they rely on most for news about the pandemic. And, according to a survey by Gallup, Americans say there are two main sources of COVID-19 misinformation: social media and Donald Trump.

The public do not understand logarithmic graphs used to portray COVID-19. New research on how people (mis-)understand graphs about COVID-19. Linear graphs make them much more fearful and they don’t understand logarithmic charts.