by Vincenzo Marino – translated by Roberta Aiello

«The most honest homepage possible»

image via

image via

This week Ben Bradlee, former editor of the Washington Post, died at the age of 93. As reported by many, he was considered one of the architects of the transformation of the newspaper, leading it to global notoriety, and managing it during Watergate, one of the most important examples of investigative journalism of all time. In an article titled “Ben Bradlee and the future of journalism,” Brian Stelter of CNN Money recalls a famous sentence reported in his 1995 memoir, «Put out the best, most honest newspaper you can today, and put out a better one the next day.» Is it still possible to hope for the next day? Or are we speaking of temporal and professional categories that don’t have too much sense anymore? Stelter quotes the essay «Bad News About The News» by Robert G. Kaiser. Due to the collapse of efficient business models, «news as we know it is at risk.» A risk that the example given by Bradlee would try to avoid. «He viewed the world like the young reporter he started as,» explains Carl Bernstein, his longtime colleague at the Post. The same reporter that today, concludes Stelter, would try to «put out the best, most honest home page you can this minute, and put out a better one the next.»

Whisper – an app that allows the sharing of ‘secrets’ and promises to guarantee anonymity to its users – has proposed an editorial partnership with the Guardian, which would have guaranteed the newspaper «newsworthy» stories and profiles. Through this contact, however, the newspaper has discovered that Whisper users are tracked (even when their geolocation is off), some information is shared with the US Department of Defense, and its data is stored and protected. The publication of the news has provoked a broad debate, since, according to the accusation by some, such as Henry Blodget (CEO of Business Insider), the newspaper has trampled on the boundaries of professional ethics – the Guardian has betrayed the “good faith” of Whisper, which relied on what the senior editor of Fortune defines on Twitter «implicit privacy.» Ryan Chittum of the Columbia Journalism Review has a different opinion. The comments of an ethical nature, he explains, need to be raised against Whisper, «and not just over how it handles its users’ data and how that differs from its promises to them.» Not disclosing this news «would have been a journalistic lapse» for the Guardian, although the editor in chief of the app, Neetzan Zimmerman, (the former viral-expert at Gawker we have mentioned here) or other Valley businessmen speak of «journalistic fraud.» «The ethical questions are all on Whispers.» The debate is still open.

What’s Facebook for?

image via

Being an inexhaustible source of “newsworthy” stories is an important part of the relationship between a social network and journalism. This week, one of the most discussed posts is published on Medium by Tory Starr, social media producer at Public Radio International. According to Starr, the debate on the spread of news on Facebook, how it works (on this issue it is interesting to read “Tell Everyone: Why We Share & Why It Matters” by Alfred Hermida), how to exploit it and how much is it a dominant factor in media distribution (here, a post of Frederic Filloux), distracts critics and journalists from a fundamental fact. Facebook is not only “distribution”, it is also an opportunity to make journalism. It is an important – perhaps the main – source of visits of course, Starr explains, but it is also «a vast repository of stories from around the world.» Graph Search, Facebook’s search engine, allows the making of research and filters it through nodes and connections of users and contents. Starr gives an example: «I was chasing a story about the Hong Kong protests and wanted to find someone to talk to. I would try these combinations in Facebook’s graph search: ‘People living in Hong Kong who speak English’ + ‘People living in Hong Kong under the age of 30’ + ‘Recent photos from Mong Kok’ + ‘Friends of [JOURNALIST] who live in Hong Kong’» (slides and examples are in the post.) Starr concludes her analysis inviting us to stop worrying so much about the distribution and promotion of content, and rather to focus on the opportunities.

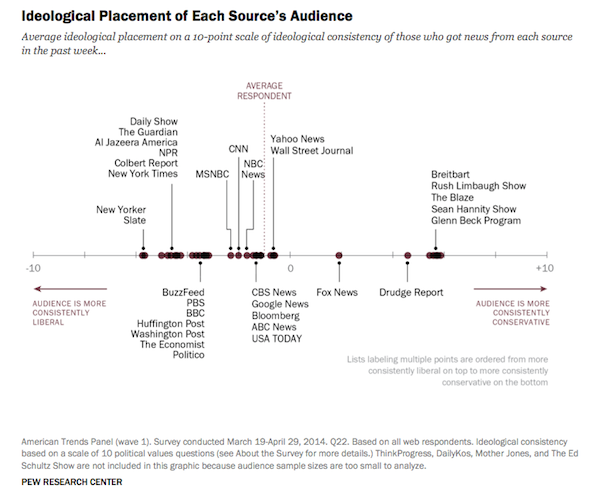

It is obvious that Facebook is a substantial part of the ‘social’ and ‘intellectual’ life of people, through research and reading of the news or political participation in various ways. This week, the Pew Research Center has sought to provide some numbers through a search on the political polarization and media habits on the Internet, based on a sample of 3,000 Americans subsequently divided by political categories (from “very liberal” to “very conservative”). The outcome of the study supports the thesis of “filter bubbles”, which are small closed ecosystems of users who discuss and read news closest to their interest. According to the research center, for example, the majority of people on Facebook consume content that is already close to their political ideas. This is all the more true if the number of users who get political news on Facebook is also considered, which reaches up to 48% of respondents (compared with 14% of YouTube and 9% of Twitter). For these reasons, it is not surprising that the opinion of journalism and newspapers is strongly influenced by how people get there. While outlets such as Politico, Economist and BuzzFeed occupy market segments defined as “niche”, political polarization leads Republican readers to focus around the pillars of area journalism (FoxNews and Rush Limbaugh above all) and Democrats divide themselves between the Guardian, the New York Times, CNN, MSNBC and TV programs like The Colbert Report and The Daily Show.

image via

image via

The market of fake news

Part of the Pew Research Center’s study focuses on the credibility placed in the major newspapers, and how this varies on the basis of the political ideas of the interviewee. It turns out, for example, that Democrats and Conservatives seem to be fully in agreement on a couple of things. The opinion on the Wall Street Journal, which is considered a reliable source whatever the political colour is, and the very low confidence in BuzzFeed (although only less than 40% of respondents had an idea about what it is.) The website edited by Ben Smith is the only «more distrusted than trusted» example of alternative journalism, regardless of political stripe. A fact that the editor comments on: «Most of the great news organizations have been around for decades, and trust is something you earn over time.» Of course, the combination of high and low, disengagement and engagement under the same roof is a complicated exercise to carry out – and the web audience does not lack exemplary episodes from which to take inspiration to analyze the phenomenon. In July, John Herrman of The Awl spoke of the «Borowitz Problem». Borowitz Report is a satirical column in the New Yorker whose paradoxical news is often taken seriously by online readers, because they are published under the banner of the historic newspaper and thus believed to be reliable – it is the same reasoning for BuzzFeed, but in reverse.

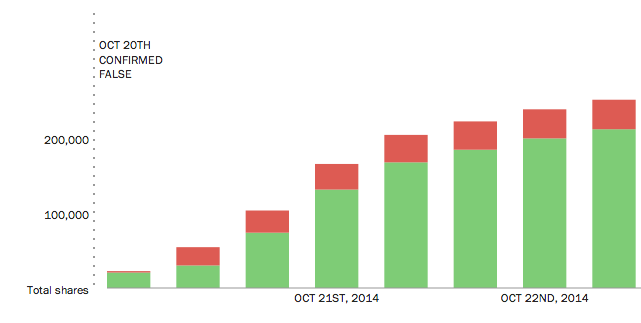

This week, many read the news of the arrest of the artist and writer Banksy, which turned out to be a hoax of the ‘specialized’ website National Report. What is the influence of the “satirical” articles in people’s news diet? And why are they taken seriously? Josh Dzieza of The Verge analyzes, using examples and graphics, the phenomenon of “fake news sites” – not those in The Onion style, with content «absurd and funny enough that most people paying attention can’t mistake it for real news,» but those who publish plausible falsehoods, particularly active recently, due to the Ebola issue. Fear is one of the elements which these fake newspapers play on, in a more and more sophisticated way, seeking to capitalize with easy clicks and shares, basing their content on a fast-setting “spectrum” (ISIS, infections and quarantine, and socials that charge) to convey on Facebook. The social network is, in fact, the major vector for news, facilitated by recurring behavior such as uncritical news sharing, without reading, source, reliability (it takes «just a headline and a caption».) What is most worrying, according to data revealed by Craig Silverman – who is trying to study the phenomenon and de-mine it through Emergent.info – is that the hoaxes are running so much faster than their debunking. «The Banksy hoax was quickly debunked by 12 different sources, and for a while the truth was winning out over the lie, but three days later the fake story has been shared almost three times as often.»

Chart by Emergent.info: “Banksy getting arrested”, spread of hoax (green) and debunking (red)