by Vincenzo Marino – translated by Roberta Aiello

Informing to stimulate action

Last week, a fire destroyed the Manchester Dogs’ Home killing dozens of dogs. The Manchester Evening News broke the news and followed with updates. Many people were worried about the century-old historical structure which is a local institution. The visits to the website of the newspaper continued to rise hour by hour, and after the umpteenth message which said “what can we do to be useful?” on social media, the editorial staff decided to launch a fundraising campaign with the aim of reaching at least £5000 to donate to the Manchester Dogs’ Home. After nearly 24 hours, the total amount of donations was more than one million pounds offered by 105 thousand contributors. David Higgerson of the Trinity Mirror wrote about this story on his blog. “Newsrooms need to understand the power of social media,” he writes. Not only to get page-clicks, but in understanding “how to respond to what people are saying on social media.” Being situated locally can offer a solution.

It is the concept of community (we talked about last week) applied to digital platforms. Local journalism continues to remain strong says Higgerson, who is the head of regional news for Trinity Mirror, especially on social media where people linked together by geographic proximity and by similar concerns can gather around an issue or a single problem and discuss it. It is the responsibility of journalism to try to find solutions, as it is pure journalism – he continues – ‘sniffing the air’ to figure out what is interesting to the readers and what they want to read. According to Mathew Ingram, journalism also means involving readers in practice, not only from the point of view of information. “It isn’t just about informing people,” he writes on GigaOm about the Dogs’ Home episode, but “it’s also about helping them take action” and engaging on instances that can really make a difference in their lives and for the common good.

A “solutions journalism” able to enrich

| ̄ ̄ ̄ ̄ ̄  ̄| | FUTURE | | OF | | NEWS | | _______| (\__/) || (•ㅅ•) || / づ

— Neetzan Zimmerman (@neetzan) 16 Settembre 2014

According to a study, articles that can provide solutions create more involvement – and are much more widely shared on social media – as opposed to those which merely recount or explore the problems. This week Catalina Albeanu of Journalism.co.uk cites the research done by Cathrine Gyldensted, a journalist who teaches at Denmark’s School for Media and Journalism.”We know that a sense of sadness,” resulting from news based on unresolved issues “leaves people depressed and inactive.” In contrast, a different perspective, focusing on solutions, helps to increase the sense “of hope and a willingness to act.” David Bornstein of the New York Times adds that journalism must not only serve to stimulate precise feelings in readers, because it has a much larger and more challenging role. What cannot be ignored – he says, citing his experience as an expert in “solutions” journalism of the Times with his “Fixes“column – is that you have to listen to feedback of readers, to be open to their solutions and their ideas. By coincidence or not, he concludes, his stories are often among the most emailed of the NYT website.

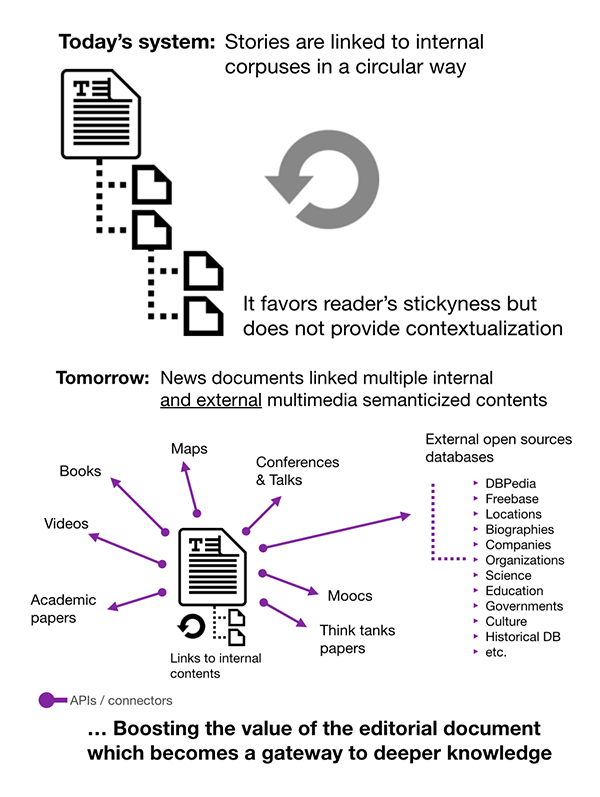

One of the strengths of this proposal is to provide the readers with all the tools they may need to frame the context, continue to learn, be passionate and then ‘get used’ to news (and maybe to subscribe to the news outlet that gave them the instruments). This week Frédéric Filloux of MondayNote analyzes how to add value to the news, unlocking them from simple commodity contents. His idea is a new type of “hypertext” that is not limited to the correlations for tags and links to sources – mostly internal to the same website – but to build a shared, common and codified language (semantic improvements) so as to make it easier to exchange knowledge from website to website (via tools such as API, Application Programming Interfaces). A kind of “lingua franca” which, in the future, could transform a simple article into a collector of multimedia information gleaned from multiple sources and aggregated into a piece complete with all relevant information to contextualize the news. The task of the journalists, at that point, is to be able to direct the reader to appropriate and reliable sources and to see their credibility and their social utility grow – which after all is the primal purpose of the profession. The diagram that Filloux proposes on his website about this issue is this:

Understanding readers by analyzing the data (but maybe it’s too late)

All of these journalistic approaches cannot avoid a careful observation of user behavior, whether it concerns grasping the idea of a fundraising for a dogs’ home, or giving the reader the right tools for understanding and reasoning. One of the examples to follow, according to the CEO of Webbmedia Group Amy Webb, is that offered by BuzzFeed. “You may not approve of their editorial content, but you must learn from their digital strategy,” focused on the comprehension of the behavior of readers, pandering to them as far as possible in offering journalism. The call of Amy Webb comes from the ASNE-APME Conference, which hosted her speech focused on this issue. It is necessary to prefer the platform to the product, the reader to the reading device. Hence, the importance of understanding user behavior and to react accordingly. “Who is your reader?” is the question that must perplex journalists and newsrooms that are supposed to get to the bottom of all the data they can to get in order to best frame and involve them (“It’s just data science”). Here you can find the slides of Webb’s presentation. Below, there is a timeline of tweets with the major points analyzed during her speech.

Meanwhile, tech companies (although not exactly journalistic) continue undisturbed in the collection of users’ data, building their fortunes in so doing. Facebook and Google, at least from an advertising perspective, know better than anyone else how the user behaves on the net, what he prefers, what kind of person he is. “The war of user data is a war that news companies have lost,” explains Joshua Benton of NiemanLab. “Print advertising continues its steady decline,” but for most news companies, online advertising growth isn’t enough. “The new money goes to the digital giants, not the local daily.” A prospect that the editor of the renewed Financial Times Lionel Barber tries to overturn. “The newspaper is still a very valuable property,” he explains to the Guardian, “anybody who said after the post-dotcom boom that print is dead is wrong.” The paper still has a valuable advertising proposition and “we can walk and chew gum here: produce a great newspaper and a great website and content for the mobile era.”