by Vincenzo Marino – translated by Roberta Aiello

This week the online journalistic debate has developed mainly on the case which involved the journalist Nate Thayer and the Atlantic. Last Monday, Thayer published his email exchange with Olga Khazan, the global editor of the magazine, who had proposed to publish one of his articles – about the relationship between basketball and diplomacy with North Korea – in the online version. The piece should have been edited and reduced from 4,000 to 1,200 words and done for free.

“We unfortunately can’t pay you for it – she wrote him – but we do reach 13 million readers a month”. The journalist explained his reasoning for his refusal – I have to “feed my children”, “I have bills to pay” -, also decided to publish the entire exchange on his blog. This causes a huge debate on websites, blogs and Twitter about the role of freelance journalism in a context of crisis, new online production methods and challenges which aspiring journalists should accept to be able to enter the profession.

The hard life of a digital freelance journalist

Felix Salmon of Reuters was among the first to intervene. He highlighted the evolution of the online journalistic profession, aimed at becoming a writing, reading, and aggregating team process that cannot contemplate only simple textual production. Consequently, comparative pay levels become less clear. Along with the production model, the economic prospects of freelance journalists would change radically and they would no no longer be able to live solely on this type of activity.

Analyzing the basic economic reasons, almost all of the media company budget is used to pay the permanent members of the editorial staff, Salmon added, causing a progressive thinning of the portion of investment dedicated to external collaborators and making this an uneconomical approach for the profession. It is possible to make profits with digital journalism, Salmon specified, but it is clear that under certain conditions, and without the certainty of an open-ended job, the field has become almost disadvantageous: “It’s fair to say the web is not a freelancer-friendly place”.

The value of work and ‘visibility’

“The economics of writing have changed,” says Mathew Ingram in PaidContent. Of course, the Internet, adds Kelly McBride in Poynter, has totally messed up a stable pay scale, based on the simple word count, which started from a minimum of 10 cents and upwards. The web, product reformulation and the distribution-content divide have ended up remodulating this equation. It can no longer rely just on the written lines because there are no precise references any more, nor – as seen before – is there the univocal impression that on the web the job is only at the textual level. This leads to the rethinking of the value of the work itself, and how it should be paid in a scenario ever more open to competition and less convenient for those who land there. Choire Sicha has posted in The Awl a long, open conversation on Branch, which involved numerous experts with many different points of view about the value of the freelance profession and its corresponding payment.

It is no longer possible to compete and survive in a scenario ‘doped’ with the introduction of new players, less and less professionalized, who offer their work in exchange for the promise of increased visibility – like the successful model of portals such as Huffington Post. More and more often, in an attempt to meet this supply curve – lowering their financial claims – the journalists themselves offer an entire catalog of free content. They behave this way in exchange for a ‘reputation’, in “a vortex of hope and hard work” (Karen Fratti in Mediabistrot) that ends up contributing directly to the collapse in guaranteed salaries – as recalled by Matt Yglesias in Slate. In this case, the editor of The Atlantic proposed a similar exchange quoting the total of the monthly visits of the website as a counterpart to the required editorial commitment.

Commenting on the story and the post of Salmon, Mathew Ingram notes how the author of Reuters has, perhaps, underestimated a particularly interesting fact. The Atlantic, which subjected the freelance to an undoubted humiliation despite the “no offense taken,” could easily excerpt chunks of the article of Thayer, citing and linking to the original, as often happens in other websites like GlobalPost or the HuffPost (crossposting). In that case how could a journalist quantify the fame returns through a simple external reference? Would it make any sense to distort a laborious professional work, agreeing to read your own article in chunks, on different platforms, without being paid? Journalism, recalls Phil Carr in PandoDaily, is a kind of vocation that takes more than 40 hours per week, and requires hard work, passion, travel and time for editing of articles which are worth the effort spent. “Now as amazing as writing for free is – Yglesias continues in Slate – there are still good reasons to refuse to do it. For example, maybe, you don’t like writing; you’d rather spend your time writing-for-free for a different platform (your own blog rather than the Atlantic); you have an offer to write for someone else for money instead”.

‘Write for free – it’s an opportunity’

According to many, the current economic outlook would not recommend a ‘strong and pure’ approach which could become counterproductive and hinder the progress of the career of an author. “If you do enjoy writing and you don’t have a money-making writing opportunity, you should definitely be writing for free”, Yglesias says. Other authors who have taken part in the debate have added, working as a collaborator for free, could be regarded as a necessary – albeit disadvantagous – approach phase in the climb that should lead to the ‘permanent’ job. “Contrary to the opinion of some of my media colleagues, I’m thrilled there was an opportunity to be a poor freelance blogger”, explained Gregory Ferenstein in TechCrunch. “If it weren’t for underpaid writers, I never would have had the opportunity to be a journalist”.

Even Jane Friedman, in “The state of Online Journalism Today“, admits that she could have accepted the offer of The Atlantic, although it depends on the work situation and the sensitivity of the individual. “Based on Thayer’s career profile – already an appreciated reporter specialized in Southeast Asia affairs, A/N – it’s easy to see why he said no”. From the same pages of The Atlantic, Stephanie Lucianovic defends unpaid work, justifying the choice of the free-of-charge collaboration, aiming at the freedom of artistic expression. “I don’t always consider writing ‘work‘. Sometimes writing just happens”. It’s a personal act for which you think – and hope – to be paid for, however, it has been carried out by the author anyway, without much effort.

The Atlantic‘s stance

The strongest and most precise reply comes from Alexis Madrigal, senior editor of The Atlantic, in a long article that explains the reasons that led to this dispute. Madrigal points out that he often prefers to hire a new full-time member than pay a freelancer, after assessing the pros and cons of content of external authors. All the more so, he says, if 90% of visits to the website comes from pieces written by components of the ‘team’ where there is 95% used of the invested ‘editorial’ capital. Apologizing to Thayer, Madigral agrees with the unpredictable evolution of the editorial scenario. The landscape has completely changed, it is totally different from what was imagined for years. Access to the profession and a decent economic perspective appear to be actually unsafe. None of the models so far tested, in the magazine field, seem to really function.

Meanwhile, The Atlantic has sought to explain and defend its position on several fronts. Questioned by Salmon, Bob Cohn, the editorial director, spoke of an error by the editor and admitted that maybe it would have been better to carry out a simple crossposting, without necessarily opening the topic of unpaid wages with the author, as is standard in this type of publishing practice. On his blog in The Guardian, Roy Greenslade points out that The Atlantic almost certainly does not generate profits for the owner David Bradley and his team. In another layer of irony – Salmon notes in an update to his post – it turns out that Thayer’s piece itself was deeply indebted to – and yet didn’t cite or link to – an article on the same subject published in The San Diego Union Tribune in 2006.

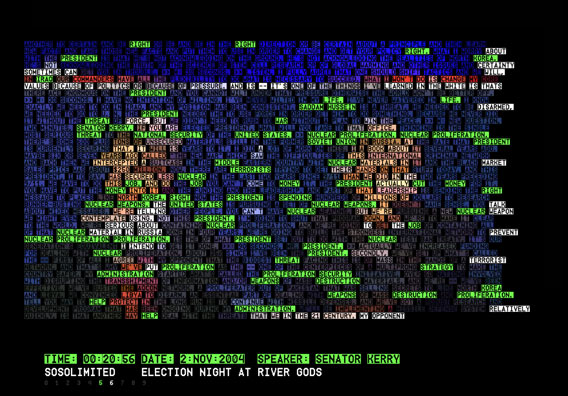

Photo via PandoDaily