by Vincenzo Marino – translated by Roberta Aiello

Trust in traditional media

Every year the Reuters Institute publishes a report on the state of journalism, in particular, on the reading habits of users. Search results for 2015 (which can be read here in pdf) have been published this week, and as outlined by Mathew Ingram of Fortune, they report both good and bad news for those who work in the media industry. “But mostly bad.”

One of the most relevant items to emerge from the study is the comparison between online traditional and digital native media (ie, the website of the New York Times on the one hand and outlets like BuzzFeed or Huffington Post on the other). If in some countries such as Germany and the United Kingdom the first prevails, in others like USA and Japan the latter are preferred by readers. This is a confirmation of the fact that universal rules are still far from being found in the digital scenario.

The worst news of the research, however, concerns traditional print media. While the very low willingness to pay for news may already seem worrying, as emerged from the report, some other graphs show how the crisis is far from being temporary and purely economic.

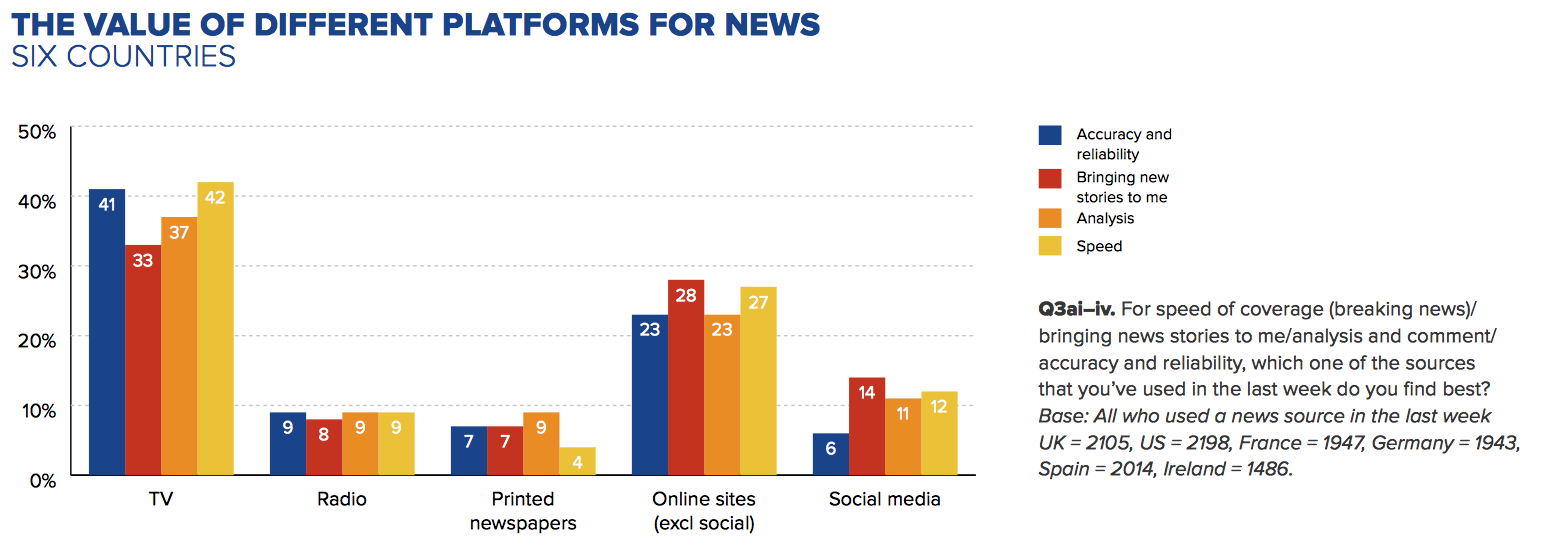

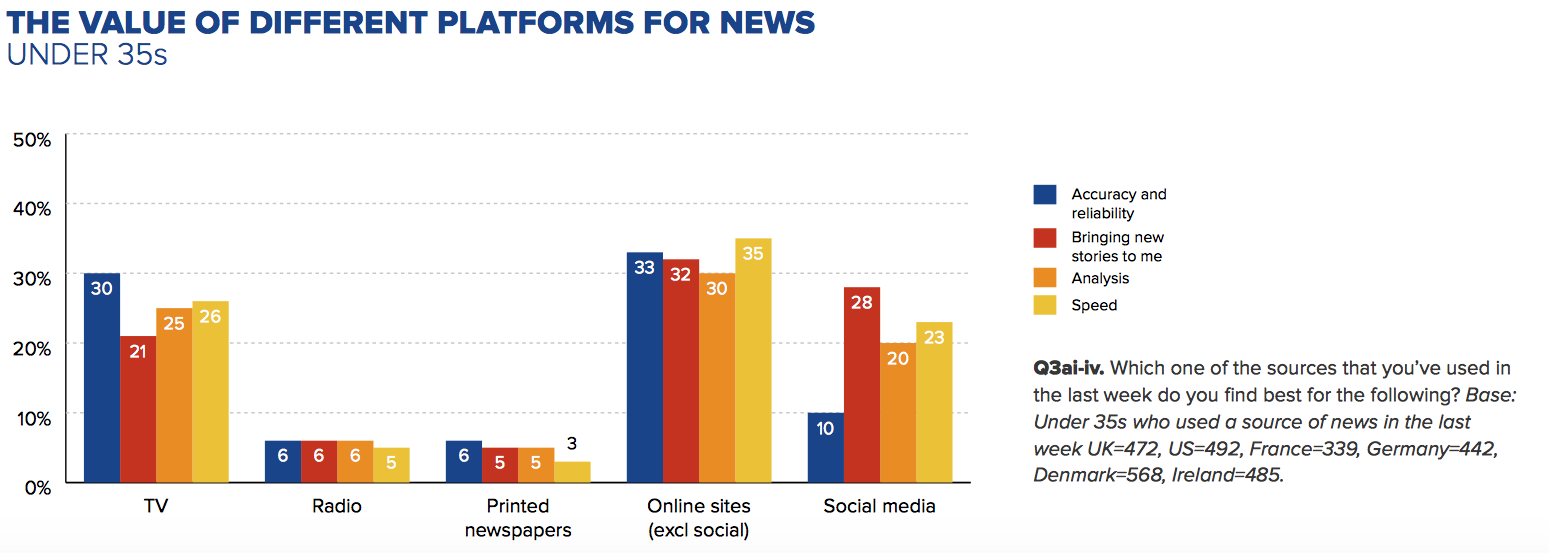

Among mainstream media, print media is considered the least reliable, the least updated, the least “profound,” both from taking a general sample (composed by readers of UK, Germany, France, Spain, USA and Ireland), and limiting research to the under 35s.

According to George Brock, the reasons for this crisis are the very low confidence among citizens towards their leaders and politicians. In this sense, the bad numbers of print media – Brock highlights – get even heavier in those countries (like USA, France, Spain and Italy) in which a very significant part of the electorate refuses to be informed about what happens on the political level.

[tweetable]”Trust in the news media, or lack of it, is inextricably bound up with the credibility of the political elite”[/tweetable]

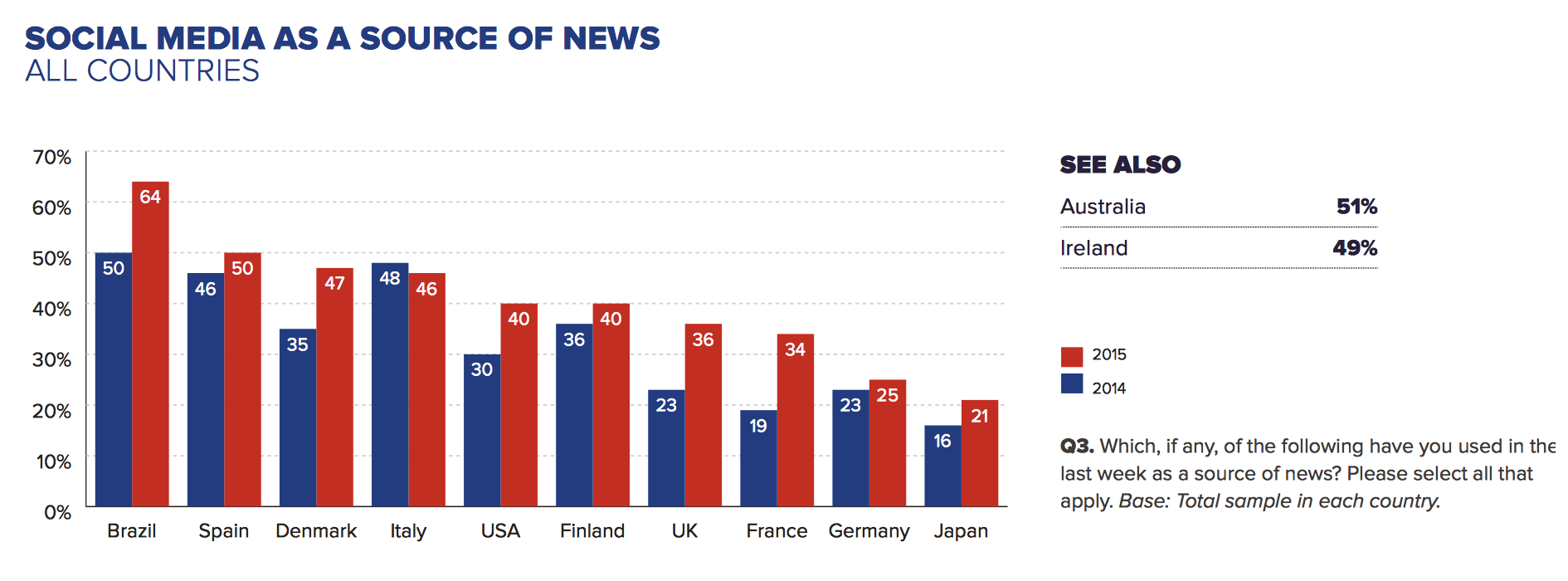

Moreover, as noted by Felix Richter of Statista, fewer and fewer people consider “print media” generally relevant, especially if confronted with an unshakable competitor such as television, or the fierce and fast growing demand for online and social media.

Mobile and social networks that “shape” journalism

.

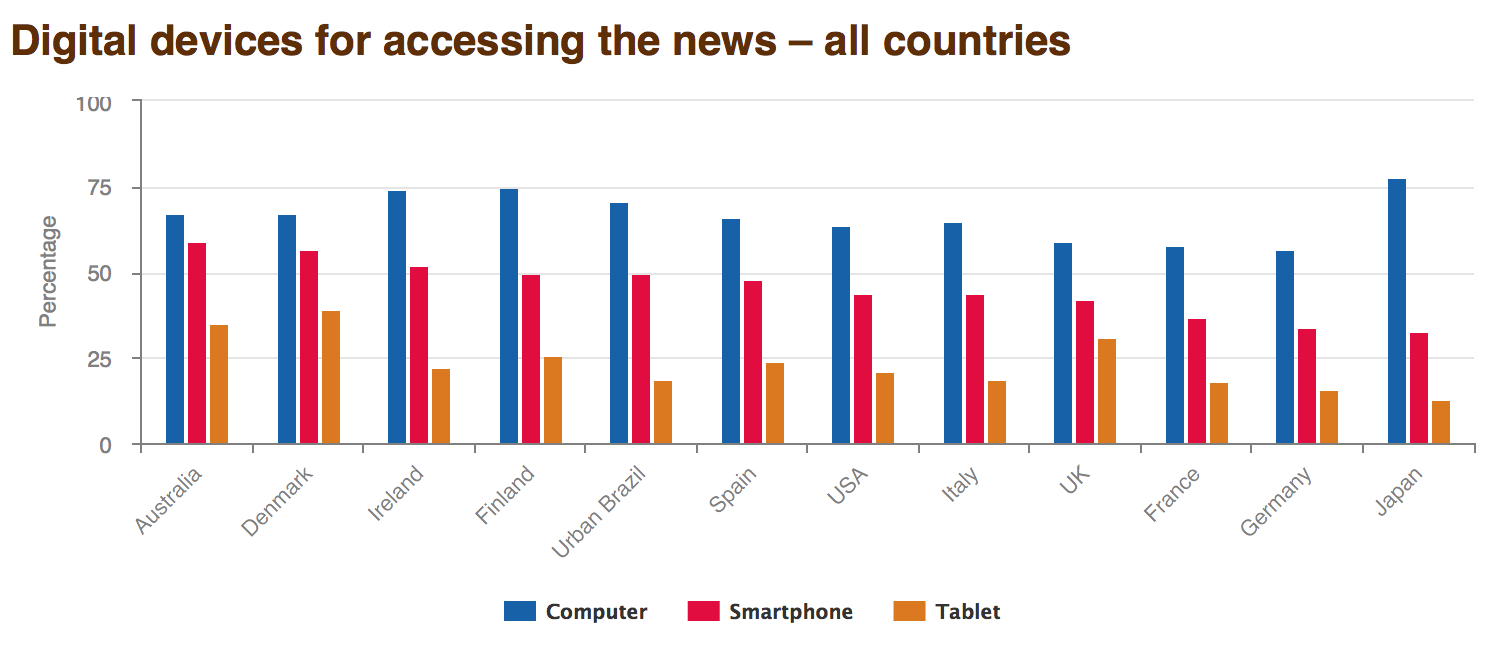

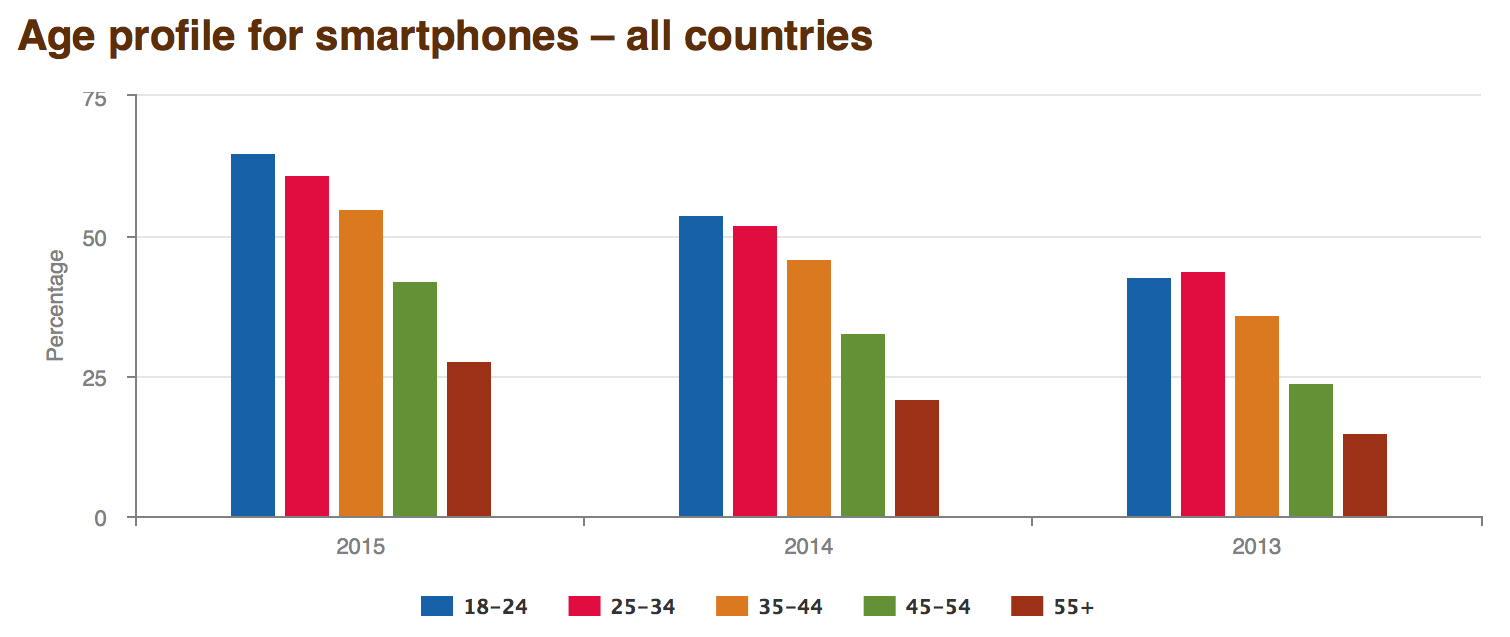

From this point of view, it is now clear that the mobile industry dominates – or is destined to dominate – the entire landscape. The figure emerges from the 2015 Digital News Report which confirms the numbers we mentioned, a few weeks ago, about the increasing use of smartphones as a news tool. More than 65% of users of mobile tools reached by the Reuters survey admit to reading the news from a device at least once a week. The mobile is the main reading tool for 40% of respondents of those under 35.

Not surprisingly, for a long time some outlets have been preparing for a switch that appears as increasingly imminent – especially looking at the growth rates of mobile news consumption by the youngest users.

This week, for example, the Guardian has presented the Guardian Mobile News Lab, a research project with its base in the American newsroom – built thanks to a $2.6 million grant from the Knight Foundation – that will focus on research and testing of new models of construction and distribution of news on mobile devices.

Distributing news on such devices, however, means mainly working with and on social networks. If the trend of reading news on the mobile is on the up, the credit is almost exclusively due to social networks, especially considering the fact that, via mobile, news is mainly read through mobile browsers, those integrated into the social networks apps, or social networks themselves – and not through the apps of the news outlets.

It is not surprising that Facebook represents the main resource for news to more than 40% of those surveyed. Commenting on the results of the research on the Reuters Institute website, Emily Bell tries to draw some conclusions. Bell wonders if for years, in times of citizen journalism and web 2.0, we have been asking who the journalist was and what made him so, maybe today the time has come to ask: “Who is the publisher?”

The news outlets were due in some way to come to terms with platforms such as Facebook. Media companies have been shaped – making their fortune – around models built on the needs of social networks and their numerous, essential users. The effect which has emerged however, summarizes Bell, is that from simple platforms full of precious readers to intercept, services like Facebook are actually “shaping journalism.”

The “Facebook addiction” is an issue that we have mentioned several times. However, data on the use of social platforms for getting news, as already seen, is becoming less equivocal, and the episodes that can animate the discussion – beyond the agreements between Facebook and publishers – are not lacking. This week, Mathew Ingram cites the case of photojournalist Jim MacMillan, who discovered that a photo on his profile had been deleted with no apparent explanation.

(Update: Check my latest comment below.)I’ve been scrubbed.Last month, I happened upon the scene after a woman was…

Posted by Jim MacMillan on Sunday, June 14, 2015

“As a corporate entity, Facebook has every right to delete or censor whatever it wants,” Ingram points out. “But what happens when that network wants to become a platform for journalism?”

“Who’s the publisher?”

.

Reported.ly, the social-oriented outlet founded by Andy Carvin and published by the group of Pierre Omidyar FirstLookMedia, is looking in some way for a compromise, as reported this week by Justin Ellis of NiemanLab.

The idea – as already seen – was to collect and provide information on various social streams in a different way. To succeed, however, to get out of the “Twitter-obsessed” circle and tell stories in a less hectic way, setting points and providing a readable framework, Reported.ly has recently launched its own website, which collects social-produced content, providing reviews and exploring some specific topics, increasing the longevity of content – which generally is not high on social networks.

It is not easy to answer Emily Bell’s question “Who’s the publisher?” Certainly an element that can enrich the debate, maybe changing it in a decisive way, comes from the last keynote of Apple. Among the additions provided for the new operating system for the iPhone there is a feature called Apple News. It is a kind of Flipboard, it has been said, that will aggregate some media partner feeds.

This week, however, it emerged that Apple is looking for editors who can aggregate news to be included in the application, changing the idea from the creation of a kind of journal based on algorithms and RSS to page curation and a proper journalistic “human” newsgathering. For many, the move sounds like a direct involvement in the journalism field by the Cupertino company, something that will not avoid – as read on 9to5 – some crucial questions.

The doubt raised by many is how news selection can be trusted when made by a company which might have an interest in favoring some sources or some news at the expense of others. Aggregators like Flipboard provide a minimum of editorial selection, but – says Marci McCue, head of Marketing at Flipboard – the center of curation is entrusted to the same user, who creates magazines and contributes to those of others, building a collective and plural aggregation.

The construction of stories starting from the contribution of users/readers is the heart of one of the proposals launched by the Guardian in the past few days. It is The Counted, an interactive project started in early June in which the newspaper calls on its readers to build, along with journalists, some kind of database to record all the deaths caused by police.

Mary Hamilton, Audience Director of Guardian US, has explained the project. On The Counted it is possible to report names, photos, any kind of information, on which reporters will then work to check and to uncover these stories, building a model of “crowdsourced” journalism based on extended networks and connections which journalists by themselves could never have done alone.

The participation of the community, and the listening by the editorial staff, is the backbone of this experiment. The hundreds of tips and submissions would never have arrived , says Hamilton, without the bond created with readers, who are animated with the willingness to listen to the outlet – on Facebook too – and the prospect of taking part in something useful.