by Vincenzo Marino – translated by Roberta Aiello

The advantages of online journalism

image via

For years, experts in the field have been focused on the advantages brought to journalism by the Internet. The ‘theory’ becomes more interesting and useful when empirical evidence is found or if there are already samples to analyze or to refer to. This week, Alison Gow Digital Innovation Editor at Trinity Mirror has written a post on her blog to consider what the new opportunities for media in a digital scenario are, making points and quoting some cases. Her list ranges from the ability to create multimedia products as much as possible, telling the story beyond an exclusively textual approach (example: this tool to tell stories of the First World War) to the need to create content that makes sense for mobile media («If it doesn’t work on mobile you need to ask yourself why you’re doing it at all»,) from the involvement of readers in the construction of content on social media (here are some tips by BBC journalists,) to the study of behavior during reading, always remembering that digital journalism is not «the freeloading cousin» of the print product.

One of the issues which Gow lingers most on is “immersive” storytelling. With the advent of digital journalism, finding new forms of narrative has been a challenge. Over time, journalism has been learning to understand phenomena that were difficult to imagine or achieve previously. One of these is virtual reality journalism. This week, Erin Polgreen of Columbia Journalism Review has dedicated a lengthy analysis to it, calling it the «next frontier» of storytelling. Tools like Oculus Rift let the reader explore firsthand virtual recreated scenarios, and can potentially be used to complement journalism in so-called augmented reality, or let the users who wear it explore an interactive setting themselves. Polgreen cites some cases: Harvest of Change of Des Moines Register which explores a farm in Iowa, or Project Syria a «full-body experience» that allows the reader to simulate the experience of a bombing. They are very expensive experiments (Harvest of Change cost nearly 50 thousand dollars) that require the use of specialized teams, often with video game skills. An effort that might be worth doing, according to the author, if the diffusion of virtual reality headsets (Oculus Rift’s new development kit costs 350 dollars) would actually grow.

The view from the ground and the view from above

image via

Not all publishers – nor, of course, all readers – can afford this kind of technology in the short term. An immersive and engaging story of the facts, however, may come from the local level, the one that last March Paul Farhi of the Washington Post defined as «a priority», even if uneconomic («It’s not that people aren’t interested in their communities […] it’s that the economics of the digital age work strongly against reporting about schools, cops and the folks down the street».) This week Andrew Haeg, founder of GroundSource and Public Insight Network, has focused on the issue. We have an impressive amount of data about our readers and what works online, Haeg explains, we are able to «imagine a new model for community-based journalism that’s raw, reveals genuine human needs and is deeply engaging.» The author cites Yik Yak as an example, a mobile app widely used in universities as a bulletin board, which guarantees anonymity and that has quickly become a collector of ideas, information and useful trends for exploring desires and the true concerns of potential readers. According to Haeg, however, there is a problem. Anonymity is a vector of profound and hidden instances, but it is also unreliable.

It is at this point that journalism comes into play, becoming a bearer and a guarantor of a needed accountability in order to make the outlet a more credible “place” and to take advantage of the opportunity to understand problems and offer solutions in day by day life. Haeg believes that the case mentioned above could represent a good basis for thinking about the construction of a new model of local journalism, based on listening to the community («Journalism, at its best, is as much about listening as it is about publishing or broadcasting») and the credibility of the listener – the journalist. In essence, «combining the view from the ground and the view from above.»

A little over a year ago in New Orleans, The Listening Post project was launched by Internews and a local public radio station, which collects messages, ideas and comments from the community, and provides local information based on a «two-way conversation.» John Stearns of the Geraldine R. Dodge Foundation has analyzed the issue, reflecting on the theme of listening for communities and newsrooms, dividing it into five models (listening as interview, as a search for ideas and sources, as feedback, to better understand the context otherwise difficult to grasp in a closed newsroom, and to establish a relationship based on trust and transparency). This means there is still space to be relevant to readers, and to be useful. According to David Kaplan, Executive Director of the Global Investigative Journalism Network, investigative journalism still has a future, if people are involved through crowdfunding and membership, are listened to and there is a public service offer (Kaplan cites the case of the Korean Centre for Investigative Journalism, which has more than 70 thousand members.)

Maybe WhatsApp can be useful, besides check marks

image via

According to Cory Bergman, cofounder of the Breaking News app, listening to readers means understanding what they do when they click on an article, and join them in many places where they spend their “digital” life. It is needed to start thinking about metrics as «time saved» on mobile devices thanks to the published content, rather than that spent consulting it (in a sense this also means being a “service” for the reader, being useful). An app like WhatsApp, for example, is still virgin territory, inhabited by millions of users unheeded by editors. In recent months, we have talked about some of the experiments focused on this service about which, however, there was still very little data (This is why we have often spoken of “dark social”).

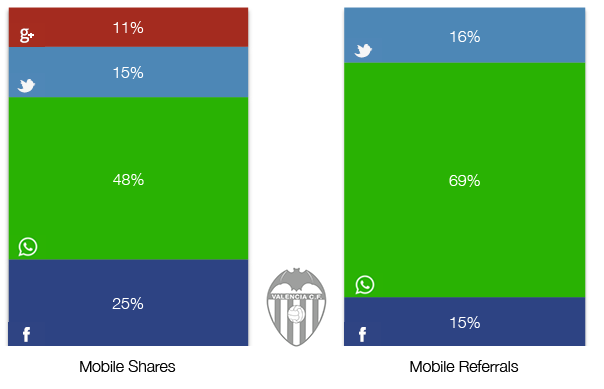

While part of the journalistic digital debate is back on the topic of the death of the web at the hands of the apps (in the same period that has shown us how the relationship between an application like Uber and journalism is, at the very least, “complicated”,) the novelty of the week, as reported by Joshua Benton of NiemanLab, is that there are those who have been able to calculate how much the use of WhatsApp, as a source of reading and sharing, may be of interest to websites. The first fact is that the search has not been conducted by a news organization but by the Valencia soccer club which, like other teams, uses the website to share content, calculating click data and traffic data.

image via

According to this analysis (which is based on the addition of a URL parameter that figures out which service the reader is coming from), WhatsApp is the “sharing button” most clicked after Facebook (35% versus 33%, Twitter 19%) and the most widely used to share posts if just mobile is considered (furthermore the “share on the WhatsApp” button only appears on screens smaller than 740 pixels wide, only on mobile.) However, there are questions. WhatsApp is widespread in Spain, as it is in Italy, but not in countries like the U.S.. For this reason, the data is still to be weighed on the basis of its geographical origin. Secondly, its communicative characteristic (providing a flow of information “one to one” – or “one to a few” in the case of sharing with a group) penalizes it in terms of viral, in a field where both Facebook and Twitter, because of their nature (one to many,) are advantaged. Benton, however, suggests continuing the study of the case, starting by analyzing the traffic from sources that are still considered “obscure,” and put the green share button of WhatsApp on the mobile version of the website. It is just a «pixel investment».