by Vincenzo Marino – translated by Roberta Aiello

Business models and clichés

The search for a sustainable system for online publishing is a classic that never stops obsessing industry experts. This week, the entrepreneur and Netscape co-founder Marc Andreessen kicked off an interesting and sustained debate on Twitter (here there is a Storify) on the state of the media and possible business models. Andreessen, who says he is optimistic, tries to analyze, tweet after tweet, the reasons that led to the decline. First of all the collapse of the monopolistic and oligopolistic market news system, in a scenario where traditional media (radio, tv and newspapers) no longer have exclusive control of distribution channels nor hereditary privileges in the process of collection, preparation and dissemination of news. Furthermore, the enlargement of its base makes the advertising market more complicated, adversely affecting the value of journalistic products (more competition means more content and a collapse of quality).

According to Andreessen the most immediate consequence was the unwillingness of readers to pay for journalistic products (and therefore the almost certain failure of any publishing project built on the paywall), imposing two types of editorial logic: the search for the niche audience (with an extremely sectorial offer) and the mainstream, with mass products. After analyzing the scenario, Andreessen theorizes what he calls “the most obvious eight business models” for now and the future:

1. Quality journalism for high-quality ads

2. Succeeding in making readers subscribe and pay for value products

3. Premium content worth buying

4. Relying on live conferences and events

5. Investing across multiple channels

6. Crowdfunding (“Gigantic opportunity especially for investigative journalism”)

7. Offering the option to pay in Bitcoin for micropayments

8. Keeping an eye on philanthropy (like ProPublica and Pierre Omidyar’s First Look Media)

The role played by quality, however, is crucial especially when analyzed in the light of the tendency of the market to expand, creating less accurate content. The challenge is to make a product (or brand) a point of reference, a “lighthouse in the night” of uncontrolled content and viral hoaxes.

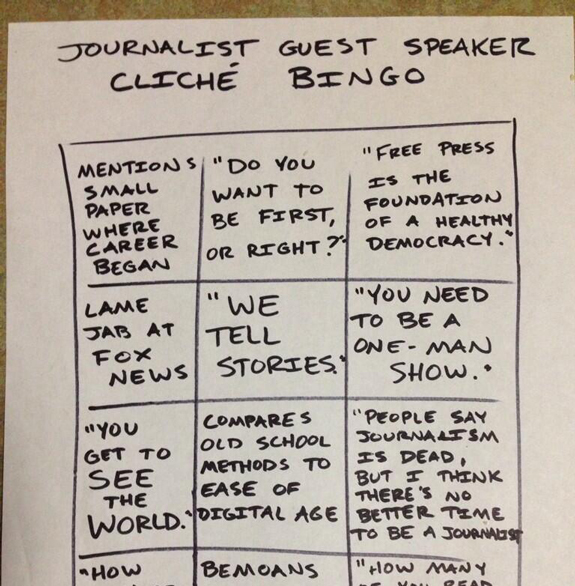

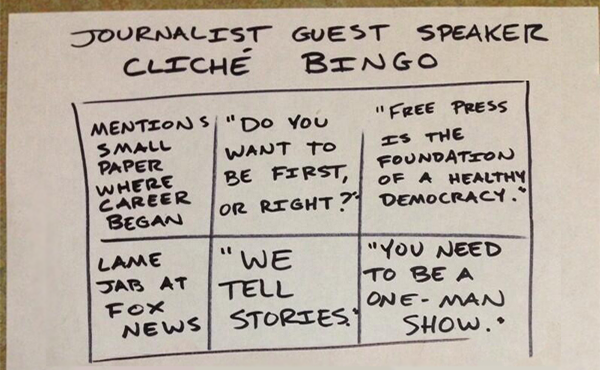

It is curious to note how the Andreessen Twitterstorm arrived in the same week as the bingo board, created by J-school students and filled with clichés used by digital publishing experts during their academic panels.

The value of digital media continues to fall

Charlie Warzel of BuzzFeed replies to the list published by Andreessen on Twitter by recalling, at the end of the post “Media Reporting’s Blind Spot”, a number of uncontrollable variables which continue to undermine the road of publishing towards a unique and unquestionably effective formula. There are methods of measuring the success of a post (Upworthy is trying), the way news is distributed on social networks, and how it behaves on the basis of ever-changing algorithms (like Facebook), trends which come and go, staying or not (listicles, GIFs, catchy titles) and young journalists who, periodically, try their luck alone (the reference is obviously to Ezra Klein). In this tumultuous market, the only certain thing is that there doesn’t exist just one model, and that – very likely – in the future, many others will emerge.

Warzel’s opinion seems to be a necessary point of view, especially if one takes the argument raised this week by Michael Wolff of USA Today (last week cited, among others, by David Carr and William Launder). The value of digital media continues to decline, despite the enthusiasm for “the better time to be a journalist” (box 3C of the bingo board). It is an optimism generally based on the idea of journalism as an essential profession, without taking into account the fact that its livelihood has always depended on heavy-duty advertising. Journalism, summarizes Wolff, has always been an ad-based market and when the advertising spending decreases, the whole structure is doomed to collapse, threatening the survival of journalism (“Advertising is the only thing that has ever paid the news bill”, and according to the chief executive of The New York Times Co., 2014 will be a “critical year”). One viable way out is to try to save money and survive while looking for professionals able to combine journalistic and managerial skills, to have “inventive commercial minds”, although at present “there are few of those” Wolff concludes.

The paywall is not enough – and it requires quality

Among the most cited models of recent years, the paywall continues to animate debate. This week, the Gannett group published its 2013 fourth quarter financial results. There was a collapse of the print circulation in the latter part of the year, against an increase in revenue due to the raising of the wall on the contents of the publications of the group (an operation which earned $100 million, described as “a success” by the company). Joshua Benton of NiemanLab fears, however, that the contribution of the paywall – albeit temporarily beneficial – is not able to ensure a fair economic security in the future. Paywalls are “a one-time boost,” sums up Jeff Jarvis on Twitter, alluding to the fact that a surge of subscriptions collected in the short term can hardly be seen as a long-term solution. It is certainly better to have $100 million than not to have it, Benton continues, but the closed structure, typical of this system, excludes from the list of possibilities the engagement of readers, doing nothing but perpetuating, with new tools, the business model typical of old print media.

The hope of Gannett, according to Ryan Chittum of the Columbia Journalism Review, is evidently to capitalize as much as possible on paid content. In the meantime, the circulation of paper declines and an all digital strategy for the foreseeable future is being sought. The problem, adds the author, is that the paywall requires quality, and that if “you’re going to charge people for journalism, you have to invest in journalism”. Tim Franklin, the new president of the Poynter Institute, is more optimistic. He considers the New York Times and the Wall Street Journal paywalls as positive examples, a viable future for the industry. Franklin talks about a revolutionized landscape where in order to assert oneself unique and original content is needed and worth investing in (the thesis of Andreessen), made more palatable by a strong brand. In this sense, he unites the experience of the NYT (the journalistic brand and the ambassador of the paywall system par excellence) to that of Ezra Klein.

Meanwhile, the Times said its digital subscribers have grown in the last quarter of the year, compared to a substantial decline in revenue from print and digital advertising. It is not a coincidence that the newspaper has recently adopted the native advertising system, which led Rick Edmonds of Poynter to wonder whether other newspapers, in the wake of the historic American newspaper, are destined to follow its example.