by Vincenzo Marino – translated by Roberta Aiello

Desktop is the new print media

There is a good chance that you are reading this post on your mobile. There are, worldwide, 5.3 billion phone users (10 times more than tablets) and of these 30% have a smartphone. Presently, the mobile industry occupies 25% of global web surfing (last year it was 14%), representing (as of 2013 data analyzed this week by Lewis Dvorkin of Forbes) 11% of global digital advertising spending, with an increase of 47%. With such data the antennae of critics and media specialists can only be pointed to the mobile future, as evidenced by the attention that the sector continues to exert on conferences, studies and academic papers. This week, for example, the Thought Leaders Summit of the American Press Institute was focused, as written by Jeff Sonderman, on the rise of mobile news, producing a report of nine key concepts on the subject. It ranges from how to present news on mobile (and what are the changes in the work of a journalist) to how to capture the attention of a “mobile” audience.

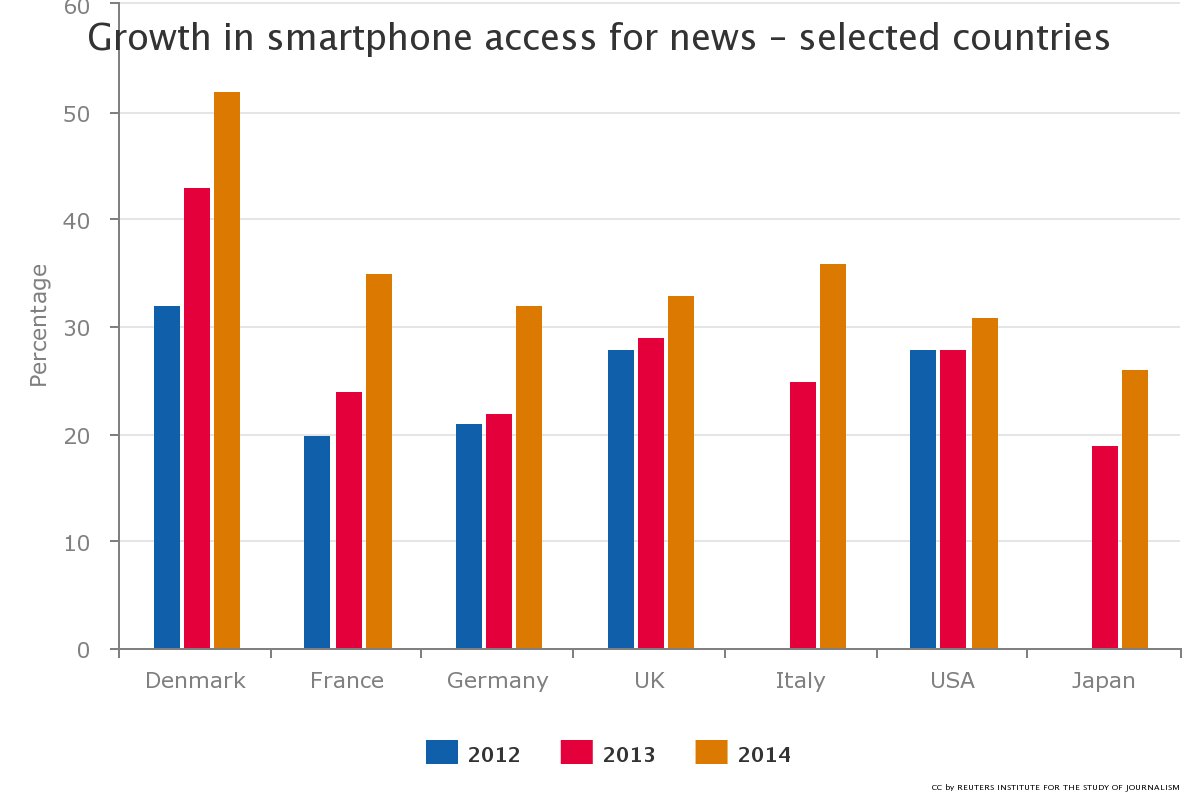

The Digital News Report of the Reuters Institute, published this week, is no exception. It dedicates an entire chapter to the rise of the mobile device, starting with the percentage of users who use it for getting their news (37%, up 6 percentage points). The example of Denmark is indicative; it is the country where the trend is most pronounced. From the Danish model we can see that smartphones alone – despite a substantial use of multi-platform news – have begun to meet a sizeable proportion of people’s news needs, drawing from a smaller number of sources than desktop surfing. Receiving too many channels of information, on such a small and basically mono-tasking instrument, is not easy – also because on a phone news must “compete” with all other channels of communication. In this respect, the role of messenger apps is crucial: one billion people in five years have subscribed to a messaging service, opening up new and uncharted territory for the news industry.

WhatsApp and others: not the how, but the what

Last February, we had already written about the possible use of WhatsApp as a news device, when Facebook bought the company for $19 billion. This week Caroline O’Donovan of NiemanLab discusses the first experiments in this direction. A few weeks ago, during the election, BBC India began to use WhatsApp to give its readers updates and provide maps, updates, tables, titles. It is true that it is rather difficult to understand how news circulates when it has been sent into the underground river of two-way conversations, and that the “viral” potential of news is greatly reduced. However, as pointed out by Trushar Barot, project manager for BBC Global, “on WhatsApp, effectively you have a 100 percent hit rate for your audience, because it pings straight onto their phone and comes up as a popup, and they will usually read it within seconds or minutes of you posting it.” It is also difficult to understand if the content can be adapted to the tool, or if the one-to-one logic can be undermined, but the focus on the how – rather than the what – seems a rather recurring obsession in the debate and on recent digital publishing news.

On the prevalence of the “means” (and ways) over the “aims” (content, themes), this week Alexis Madrigal of The Atlantic notices how the latest media startups have been overwhelmingly concentrated on the methodological aspect, rather than on the very essence of the content. “Laboratories” like Circa (in a sense very similar to WhatsApp: personal, mobile, one-to-one, with updates and popups), Vox.com, Matter, FiveThirtyEight seem more able to explain “how” they do things rather than doing them – from the mobile first to the so-called explanatory journalism (of which we have spoken with Felix Salmon at #ijf14), from dataviz to platform fetishism. It is the method that dominates, not the “area” which is meant to be covered, Madrigal continues. In spite of the fact that they are all commendable projects (he had to point out on Twitter) and there are exceptions which go in the opposite direction (Recode, First Look), this trend seems to be almost anti-journalism, because every publishing venture has always needed necessarily to talk “about something, either a topic (Vogue, Wired, Forbes) or a place (Texas Monthly, New York)”. It seems almost absurd to write about it, Madrigal concludes, “but that’s where we’re at”.

«All content deserves to go viral»

Staying on the topic, this week there has been much talk of Medium, the thing (it is difficult to define it, since the debate is still open) that lets you write and read articles of medium length, by amateurs and professionals chosen in a publishing manner. Ev Williams, the founder of Medium, wanted to launch by saying that yes, “we are a publisher” and therefore produce content as true publishers despite the platform being free access. The belated admission – with the creation along the way of the improbable neologism platisher (platform + publisher) – was given just in time for the launch – or revival – of Matter, the publishing startup we talked about two years ago (one shot articles production, to buy on a regular basis) which wants to be substantially the magazine and longform version of Medium.

I feel like every time I hear more about @Medium I understand it less. https://t.co/hD8SEAAc6M

— Spencer Ackerman (@attackerman) 9 Giugno 2014

The first article to be published in the new Matter is a long interview by Felix Salmon of BuzzFeed CEO Jonah Peretti. It is an article of 23,000 words (there are those who dared to say “We’re supposed to be post-text” referring to the article in which Salmon explained why he joined Fusion and dreamed of a production able to go beyond the text). The interview was summarized by Mathew Ingram of Gigaom and Caroline O’Donovan of NiemanLab, and is based on a few points: Peretti’s past as a sociological researcher and unconscious creator of viral content, the experience at the Huffington Post which helped him to launch BuzzFeed, the next change of direction and the science of virality, of which his creation is a very successful exemplary. The trick – Peretti explains – was to amplify what was already viral before, and then fit it to the different cultural niches of the Internet by adopting an approach that is never pedantic, speaking to the readers with their language and their “enthusiasm”, and protecting them from irritating or inaccessible content that makes them feel inferior. In this perspective, the adherence to the theory of the identification of phenomena and pop culture celebrities as a tool for the perpetuation of the capitalist model – as stated in a juvenile paper on Marxist theories by the same Peretti, published by Vox few weeks ago – is almost immediate.

Meanwhile The Onion has announced the birth of Clickhole. The idea is to follow the pattern of websites like BuzzFeed and Upworthy (catchy titles, high shareability content – and low reading) by making a parody, producing meaningless material created with the sole purpose of reproducing and mocking these publishing modes with the motto “All web content deserves to go viral.” The best way to understand what we’re talking about is to open this post.