This week in RoundUp: the report of the Columbia Journalism School on post-industrial journalism and the future of the media; the ‘brand’ journalist, for example Nate Silver; the Rudoren-NYT episode and the unexpected arrival of the social media-sitter.

“Post industrial” journalism and survival

Much media debate this week has centered on a report by the Columbia Journalism School written by C. W. Anderson, Emily Bell and Clay Shirky entitled Post-Industrial Journalism: Adapting to the Present. It can be downloaded free in pdf or as an ebook. The report sets out the current state of play and considers in detail the future of journalism, taking on board a revolution which has caused not just the disembowelment of traditional newsrooms, obliging them “to do more with less”, but which has also put up for discussion the role of the no-longer-passive reader (or, à la Jay Rosen, The People Formerly Known as the Audience) and of the journalist – not “replaced but displaced” – who now needs to interpret, verify, filter, interact and in the time left over take care of his/her personal brand. Journalism viewed this way becomes an ‘information performance” taking the place of simple and sterile “dissemination of news”. What sets the journalist apart from social media, the aggregators and the algorithms is the capacity to interpret and produce original content adaptable to a variety of platforms.

One central feature of the report is the gauntlet thrown down to journalists. The ability to stay afloat in a radically new environment will require adaptability and freshness. And whatever new economic system settles into place, it will not be able to offer the same remuneration and professional prestige that journalism guaranteed its protagonists for decades. The authors underline that it’s not a question of finding a new business model – indeed they don’t yet see a credible alternative nor a clearly-defined future publishing panorama – because the future is already here and what was once called the news industry in effect disappeared some time ago.

The report has already been widely analysed and a synthesis of the reaction it has generated has been put together by Joshua Benton at NiemanLab. One observation worth noting is by Mathew Ingram in GigaOM: the report risks finding an audience only among the converted who already know the set-up and who have been working for and within change for a while. That said, the real sense – the real moral imperative indeed – which comes forth form the 122 pages is encapsulated perhaps in the authors’ final recommendation: “survive!”

Brand name: from the High Street to the newsroom

One interesting element of the report is the attention given to the individual journalist over and above the media organisation for which he/she happens to work. Jeff Sonderman focuses on this in Poynter in an article entitled “Just the facts isn’t good enough for journalists anymore”. Readers want more than just the news. They want the personality of the journalist, his/her energy, his/her particular value added; the more readers feel encouraged to interact with journalists they feel in some way attracted to, the more they want to hear that individual journalist’s side of any story. The report emphasizes that the ability to interact effectively with readers, to utilize personality to maximise audience, to play the charisma game are not skills that are easily learned. But neither are they merely one option among many any more.

The personal brand issue is analysed by James Breiner in International Journalists’ Network and in his blog. He claims that in the period immediately prior to the US presidential elections approximately 50% of all the visits to the website of The New York Times were through Nate Silver, author of the FiveThirtyEight blog and celebrated for his remarkably precise forecast of the election results. “He got huge, huge readership. They weren’t coming for the rest of the Times; they came for him” in the words of JIll Abramson, the NYT editor. In other words, the brand Nate Silver in that particular context became momentarily almost as powerful as the brand NYT itself. The Anderson, Bell and Shirky report envisages a future scenario where some 90% of news on the web will be put together by algorithms, thus providing an opportunity for the journalist – and associated personal following – to make his/her mark through the aforementioned value added (even Gabe Rivera, founder of well-known aggregators Techmeme and Mediagazer, admitted recently that he was beginning to feel the need for a few more ‘human’ journalists).

A social media-sitter at The New York Times

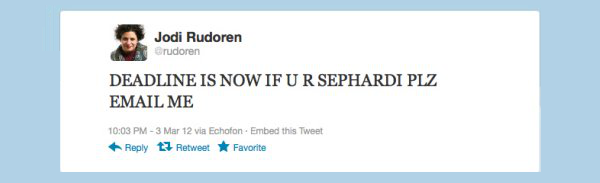

The fragmentation of journalistic writing – and its results in terms of unique visits and social media ‘influence’ – can expose the individual journalist, and by extension his/her media organisation, to significant risks. Journalists occasionally express themselves inappropriately on social networks – despite the codification of best practice, as we have seen – and their employer must then dutifully admonish and take measures to ensure no repeat in future. It happened this week to Jodi Rudoren, Jerusalem bureau chief of The New York Times.

Take any journalist who likes to interact with readers, who is spontaneous and personable, who has one of the more delicate roles in the newspaper in one of the most delicate international contexts: ”The result is very likely to be problematic” commented the public editor of the NYT Margaret Sullivan. The journalist in question posted on Twitter and Facebook personal opinions considered biased by some readers. Result: the NYT provided Rudoren with a ‘personal’ social media editor. “The idea is to capitalize on the promise of social media’s engagement with readers while not exposing The Times to a reporter’s unfiltered and unedited thoughts” explained Sullivan.

It it right, as some wondered, to undermine the freedom of expression of someone who, while having a clearly-defined professional role, is nonetheless obviously entitled to his personal views? Or, alternatively, is it right to demand the same procedures in one’s social life as in one’s professional life? Or, perhaps more pertinently, is it right to appoint a fully-fledged social media-sitter to a professional journalist as if he were a toddler likely to knock his cereal bowl off the table? The journalist concerned has stated that he doesn’t feel in any way upbraided and indeed views the development as constructive. Best practice rule number one: «don’t do anything stupid», this time with a guardian angel.